We've just passed one important little milestone that (as far as I saw) went with little recognition: English county cricket now has ten years' experience of a two-divisional structure. Having realised this, my response, characteristically enough, was to crunch a few numbers from the period.

To start with, I looked at how each county has performed throughout the decade. Table 1 collects each season's final standings into a single meta-championship, ordered according to points attained across both divisions. Data are separated according to division, with first division figures presented first and, where applicable, an overall total for both divisions given at the end.

Table 1: County championship, 2000–2009

(Div1+Div2) Bonus Points ---------------------------- Seasons P W Batting Bowling Points* Titles ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. Surrey 8+2 128+32 (42+11) 53 (408+116) 524 (338+80) 418 (1522.25+410) 1932.25 2+1 2. Sussex 8+2 128+32 (44+12) 56 (384+73) 457 (348+81) 429 (1553+342) 1895.00 3+1 3. Lancashire 9+1 144+16 (45+7) 52 (371+43) 414 (385+47) 432 (1654+212) 1866.00 0+1 4. Nottinghamshire 5+5 80+80 (24+28) 52 (219+258) 477 (210+212) 422 (896+957) 1853.00 1+1 5. Warwickshire 7+3 112+48 (35+12) 47 (335+146) 481 (284+121) 405 (1303+548.75) 1851.75 1+1 6. Kent 9+1 144+16 (45+8) 53 (376+43) 419 (385+44) 429 (1599+219) 1818.00 0+1 7. Essex 2+8 32+128 (5+47) 52 (62+349) 411 (81+332) 413 (272+1498) 1770.00 0+1 8. Hampshire 7+3 112+48 (33+18) 51 (264+112) 376 (316+128) 444 (1207.5+560) 1767.50 0+0 9. Northamptonshire 2+8 32+128 (3+44) 47 (87+363) 450 (77+331) 408 (282+1481.5) 1763.50 0+1 10. Yorkshire 7+3 112+48 (29+12) 41 (309+147) 456 (306+129) 435 (1185.75+546) 1731.75 1+0 11. Somerset 5+5 80+80 (15+25) 40 (229+238) 467 (215+206) 421 (830.75+893) 1723.75 0+1 12. Worcestershire 3+7 48+112 (4+45) 49 (99+306) 405 (115+304) 419 (350+1353) 1703.00 0+1 13. Middlesex 4+6 64+96 (12+25) 37 (197+267) 464 (168+260) 428 (663+1029.25) 1692.25 0+0 14. Durham 5+5 80+80 (27+17) 44 (190+157) 347 (220+214) 434 (893+713.5) 1606.50 2+0 15. Leicestershire 4+6 64+96 (15+19) 34 (158+223) 381 (172+241) 413 (626.5+911.5) 1538.00 0+0 16. Gloucestershire 2+8 32+128 (4+30) 34 (75+310) 385 (87+332) 419 (276+1259.5) 1535.50 0+0 17. Glamorgan 2+8 32+128 (3+28) 31 (69+320) 389 (75+331) 406 (221.5+1258.5) 1480.00 0+0 18. Derbyshire 1+9 16+144 (2+25) 27 (19+323) 342 (44+388) 432 (111+1280.5) 1391.50 0+0 * sum of points as awarded according to rules pertaining in each season, including deductions for slow over rates and substandard pitches

So, the team who have won most points overall is Surrey, though they are only fourth on the list of division one points-scorers. Mind you, the two sides who have played most seasons, won most games, and collected most points in division one cricket – Lancashire and Kent – have yet to raise the pennant in the two-division era. Surrey have also amassed most batting bonus points (both overall and in division one). Hampshire have most bowling bonus points across both divisions; Lancashire and Kent tie (again) for most first division bowling points. On the whole, there's much less variability in bowling bonus points: the lowest-scoring team – Warwickshire – are only 40 points behind the leaders, whereas Derbyshire's haul of batting points is very nearly 200 points behind Surrey's.

Because rules have changed, over the decade, some teams may benefit from having been at their strongest when points were most easily available. To get around this problem, I worked out how many points each team would have accumulated according to a uniform points system (and, because I'm interested to see if it will have much impact, I've used the schema that will be in place in 2010, with 16 points for a win and 3 for a draw). One would need more detailed information on the course of each match than I have available to me to standardise the number of first-innings overs in which bonus points can be scored (the threshold for which has also changed over the years), so I simply ignored the over-limit, and awarded bonus points for all first innings at their completion. I did reapply the deductions, though. After all that, it turns out that it makes next-to-no difference, anyway. When ranked according to all points won (as above), Hampshire and Northamptonshire swap places, as do Somerset and Worcestershire. By and large, though, it's as you were.

While I was fiddling about with recalculating points tables, I had a quick look to see if the 2010 rules would have made any difference to the final standings in any year. There are three instances in which they would have: Gloucestershire, not Glamorgan, would have been promoted in 2000; Yorkshire, not Nottinghamshire, would have been relegated in 2006; and Yorkshire, not Kent, would have been relegated in 2008. Perhaps the most interesting of these is the last. If Kent had stayed up for 2009, they would have been the only team to make it through the whole decade without once slipping from the top flight.

An unanswered question is how much real difference there is between the divisions. Because cricket is a zero-sum game, it is not possible to draw inferences from overall figures (a higher standard of cricket cannot, logically, be reflected in a higher overall batting average and a lower overall bowling average; if one goes up, so does the other). One way to get a handle on the matter is to look at how individual players have performed in each environment; one would expect both batsmen and bowlers who have played in both divisions to have inferior records in the top flight if the quality of cricket really is higher there.

And, by and large, that is what the figures show. Over the decade, individual batsmen averaged a median of 1.7 runs fewer in division one than they did in division two. A similar trend is seen on a season-by-season level: batsmen stepping up from division two to division one averaged a median of 2.3 runs fewer in the season following promotion than they had the year before.

Table 2 shows the batsmen with the greatest differences – both positive and negative – between their records in the two divisions. The top of the table lists those whose second division figures far exceed their performance in the top flight; at the bottom, we find batsmen for whom the challenge of first division cricket seems to have been a stimulus to higher levels of achievement.

Table 2: Difference between first and second division batting average, 2000–2009

Division One Division Two ------------------------ ------------------------ Name I NO R Ave I NO R Ave diff ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- RC Irani 46 2 1,211 27.52 110 23 5,462 62.78 -35.26 M van Jaarsveld 118 7 5,060 45.59 24 3 1,475 70.24 -24.65 IR Bell 124 11 4,810 42.57 21 3 1,142 63.44 -20.88 PD Collingwood 33 1 792 24.75 73 7 2,943 44.59 -19.84 JL Langer 47 3 1,914 43.50 53 4 3,093 63.12 -19.62 IJL Trott 139 13 5,351 42.47 25 5 1,240 62.00 -19.53 SM Katich 43 4 1,723 44.18 50 9 2,610 63.66 -19.48 MR Ramprakash 159 22 9,368 68.38 61 8 4,649 87.72 -19.34 GO Jones 94 14 2,644 33.05 25 0 1,291 51.64 -18.59 WI Jefferson 52 4 1,117 23.27 88 7 3,362 41.51 -18.24 JS Foster 44 0 1,036 23.55 145 20 5,177 41.42 -17.87 MA Wagh 147 11 5,048 37.12 62 7 3,015 54.82 -17.70 MP Maynard 22 0 641 29.14 93 5 3,906 44.39 -15.25 DJ Hussey 51 6 2,741 60.91 37 5 2,427 75.84 -14.93 MEK Hussey 43 5 2,497 65.71 60 8 4,150 79.81 -14.10 IJ Sutcliffe 156 10 4,764 32.63 24 2 1,016 46.18 -13.55 CR Taylor 21 1 333 16.65 37 1 1,062 29.50 -12.85 AD Brown 184 22 6,687 41.28 26 4 1,177 53.50 -12.22 SJ Walters 20 1 355 18.68 24 0 739 30.79 -12.11 A McGrath 148 10 5,372 38.93 62 7 2,802 50.95 -12.02 ... TJ Murtagh 42 18 774 32.25 62 12 925 18.50 13.75 MP Dowman 26 3 699 30.39 35 0 580 16.57 13.82 SG Law 157 18 8,298 59.70 54 4 2,249 44.98 14.72 AV Suppiah 31 1 1,328 44.27 34 0 998 29.35 14.91 TT Bresnan 68 14 1,680 31.11 38 6 511 15.97 15.14 NRD Compton 34 3 1,289 41.58 50 2 1,264 26.33 15.25 DJG Sales 25 5 1,230 61.50 171 12 7,034 44.24 17.26 A Dale 23 3 1,026 51.30 89 8 2,562 31.63 19.67 MJ Prior 152 10 5,624 39.61 24 2 433 19.68 19.92 JP Maher 53 4 2,111 43.08 35 0 761 21.74 21.34 qual. = 20 inns in each division; full list available here

It is interesting to see three of England's current top 6 in the upper reaches of this table, with first division averages some twenty runs lower than their second division figures. They may be slightly balanced by Matt Prior, who is second only to Jimmy Maher amongst those who have done better in the first division. Among other notable names in the table, it is unlikely that Mark Ramprakash or the Hussey brothers will face too much criticism for the discrepancy between their first and second division averages, given that they each managed 60+ in the top flight. The most consistent of the lot is Brad Hodge, who has 2,063 runs at 50.32 in division one, and 2,163 at 50.30 in division two.

A similar picture is seen with bowlers. Over the decade, individual bowlers averaged a median of 1.8 runs fewer in division 2 than they did in division 1. However, bowlers stepping up from division 2 to division 1 appear to have found the transition particularly challenging, averaging a median of 5.4 runs more in the season following promotion than they had the year before.

Table 3: Largest difference between first and second division bowling average, 2000–2009

Division One Division Two ---------------------------------- ----------------------------------- Name I B R W Ave I B R W Ave diff -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- PJ Franks 65 5,119 3,202 66 48.52 92 8,295 4,830 161 30.00 18.52 JC Tredwell 95 9,793 5,516 127 43.43 28 4,091 1,838 69 26.64 16.80 JF Brown 40 6,350 2,930 64 45.78 139 19,944 8,891 277 32.10 13.68 TJ Murtagh 45 3,642 2,215 57 38.86 79 7,603 4,381 168 26.08 12.78 RDB Croft 36 5,419 3,051 66 46.23 199 29,149 13,322 398 33.47 12.75 AJ Hall 62 5,819 3,027 98 30.89 53 3,564 1,743 81 21.52 9.37 DD Masters 72 6,698 3,678 101 36.42 116 12,946 5,467 200 27.34 9.08 NM Carter 106 10,419 6,307 156 40.43 30 2,812 1,640 52 31.54 8.89 DA Cosker 33 4,917 2,795 61 45.82 120 14,262 6,676 180 37.09 8.73 GJ Kruis 64 6,234 3,470 90 38.56 26 3,507 1,961 64 30.64 7.91 IDK Salisbury 114 11,658 6,242 174 35.87 43 4,878 2,527 90 28.08 7.80 PN Weekes 77 6,234 3,407 72 47.32 59 5,161 2,469 62 39.82 7.50 GP Swann 105 11,723 5,700 150 38.00 74 8,396 4,378 143 30.62 7.38 GJ Batty 58 7,199 3,611 92 39.25 124 13,907 6,635 204 32.52 6.73 RJ Kirtley 118 12,629 6,596 215 30.68 57 6,529 3,308 138 23.97 6.71 BJ Phillips 52 4,643 2,258 61 37.02 59 4,388 2,083 68 30.63 6.38 K Ali 42 4,339 2,629 84 31.30 131 12,418 7,364 290 25.39 5.90 CE Shreck 79 9,262 5,194 154 33.73 29 3,533 2,006 72 27.86 5.87 DG Cork 119 10,912 5,185 179 28.97 71 7,519 3,722 156 23.86 5.11 CT Tremlett 93 9,752 5,250 172 30.52 42 3,890 2,197 86 25.55 4.98 ... SJ Harmison 76 8,003 3,936 173 22.75 53 5,687 2,897 106 27.33 -4.58 AR Caddick 40 4,855 2,747 108 25.44 99 12,728 7,422 246 30.17 -4.74 OD Gibson 49 5,247 3,118 129 24.17 47 5,432 3,050 104 29.33 -5.16 AD Mullally 36 4,843 1,988 95 20.93 50 5,414 2,422 92 26.33 -5.40 AR Adams 33 3,838 1,818 74 24.57 53 5,787 3,110 94 33.09 -8.52 JM Anderson 50 4,786 2,577 120 21.48 30 3,076 1,813 60 30.22 -8.74 JD Middlebrook 45 5,276 2,804 84 33.38 150 15,460 8,156 187 43.61 -10.23 RL Johnson 38 4,623 2,388 105 22.74 102 10,242 5,712 166 34.41 -11.67 DL Maddy 111 6,770 3,533 127 27.82 74 3,905 2,143 54 39.69 -11.87 AJ Tudor 64 5,586 3,377 116 29.11 54 4,290 2,710 61 44.43 -15.31 qual. = 50 wkts in each division; full list available here

There's a good number of county stalwarts – and few bowlers that many would identify as being really top-rate – at the head of this list. It is this table that is most suggestive, to me, of an essential divide between the two strata of the domestic game: I find it quite hard to resist the conclusion that there is such a thing as a journeyman bowler who can do an effective job in the lower division, but lacks the penetration to transfer those results to the top flight. In contrast, there are a fair few bowlers who have managed to rise to the challenge of the first division and, by and large, these seem to be some pretty good players, to me. Mainstays of England's bowling attack in the beginning, middle, and end of the decade are amongst them: over the decade, Caddick, Harmison, and Anderson all averaged at least 4½ runs fewer in division 1 than they did in division 2.

(By the way, my eye was also caught by the fact that there's quite a few spinners in the upper reaches of the table and few in the bottom, so I looked to see if twirlers in general have found the going any harder in the top division. They haven't – in fact, they average ever-so-slightly less in the top flight.)

Taken together, this evidence suggests that, on average over the decade, first division cricket has been a couple of runs per wicket stronger than the division two game. Perhaps surprisingly, I can't detect any evidence of the gap getting any wider over time: there appears to have been a gulf of approximately two runs from the start of the period and, when I regressed season-to-season variation against year, I didn't get any significant results.

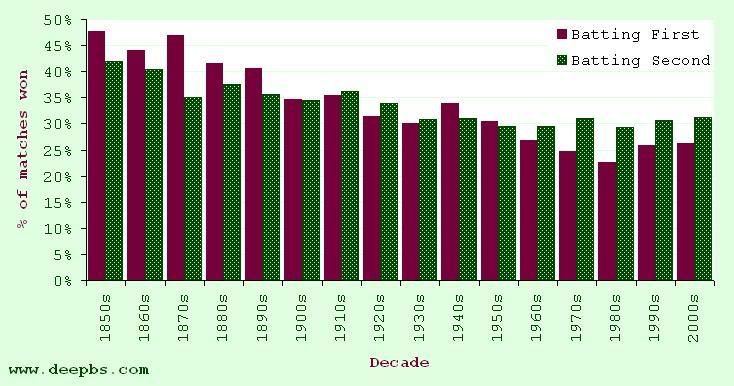

Here's a final stat to round things off. We were told that the whole point of two-divisional cricket was to increase competitiveness in the domestic FC game which, in turn, was supposed to improve the England test team. Well, it's all a bit post hoc ergo propter hoc but, in the 2000s, England won 42.6% of their test matches, which was a substantial improvement on their success-rate in the 1990s (24.1%), and their best since the 1950s. I'm sure those who were enthusiastic about the introduction of the new structure would consider that evidence enough that the reforms have served their purpose.

Anyone who's not particularly interested in Somerset can stop reading, now. Since Somerset have spent half of the decade in each division, there's a reasonable amount of data available on how players got on at either level of the game.

Note that the data are not limited to games for Somerset; it's just the overall records of those who have a Somerset connection.

Table 4: Largest difference between first and second division batting average, 2000–2009: Somerset players

Division One Division Two ------------------------ ------------------------ Name I NO R Ave I NO R Ave diff ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- JL Langer 47 3 1,914 43.50 53 4 3,093 63.12 -19.62 KA Parsons 50 4 1,324 28.78 33 6 1,036 38.37 -9.59 PD Trego 74 10 2,039 31.86 40 5 1,410 40.29 -8.43 ID Blackwell 105 5 3,985 39.85 84 9 3,558 47.44 -7.59 SRG Francis 26 13 110 8.46 37 14 351 15.26 -6.80 PS Jones 60 15 692 15.38 63 15 1,057 22.02 -6.64 AR Caddick 29 7 252 11.45 68 14 937 17.35 -5.90 JC Hildreth 51 4 1,738 36.98 97 9 3,539 40.22 -3.24 J Cox 73 6 2,823 42.13 45 3 1,840 43.81 -1.68 CM Willoughby 30 15 110 7.33 50 20 253 8.43 -1.10 PD Bowler 68 7 2,655 43.52 37 7 1,329 44.30 -0.78 M Burns 73 3 2,422 34.60 65 5 2,085 34.75 -0.15 KP Dutch 47 7 944 23.60 25 1 569 23.71 -0.11 RJ Turner 73 7 1,811 27.44 54 13 1,076 26.24 1.20 MJ Wood 65 2 2,071 32.87 83 4 2,407 30.47 2.40 RL Johnson 32 7 669 26.76 78 8 1,388 19.83 6.93 ME Trescothick 74 4 3,914 55.91 41 2 1,835 47.05 8.86 AV Suppiah 31 1 1,328 44.27 34 0 998 29.35 14.91 NRD Compton 34 3 1,289 41.58 50 2 1,264 26.33 15.25

In common with the national trend, most players did at least a bit worse in division one than they did in division two. Nevertheless, it is quite encouraging to see, at the very bottom of the table, that the three batsmen who are quite likely to make up Somerset's 2010 top three have each done conspicuously better in top-flight cricket than in the second division.

Table 5: Largest difference between first and second division bowling average, 2000–2009: Somerset players

Division One Division Two ----------------------------------- ----------------------------------- Name I B R W Ave I B R W Ave diff ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ JID Kerr 13 1,132 694 12 57.83 12 716 545 13 41.92 15.91 KP Dutch 40 3,590 1,962 46 42.65 26 2,231 1,199 42 28.55 14.10 BJ Phillips 52 4,643 2,258 61 37.02 59 4,388 2,083 68 30.63 6.38 CM Willoughby 53 6,286 2,987 103 29.00 79 8,244 4,525 161 28.11 0.89 PS Jones 86 9,776 5,695 154 36.98 94 8,740 5,323 142 37.49 -0.51 ID Blackwell 102 10,567 4,496 120 37.47 87 9,507 4,600 114 40.35 -2.88 PD Trego 74 4,954 3,197 88 36.33 46 3,061 2,045 50 40.90 -4.57 AR Caddick 40 4,855 2,747 108 25.44 99 12,728 7,422 246 30.17 -4.74 M Burns 39 2,093 1,308 36 36.33 30 1,322 754 18 41.89 -5.56 SRG Francis 28 2,056 1,381 38 36.34 54 4,678 3,123 73 42.78 -6.44 RL Johnson 38 4,623 2,388 105 22.74 102 10,242 5,712 166 34.41 -11.67 AV Suppiah 22 1,415 764 15 50.93 22 915 656 7 93.71 -42.78 Z de Bruyn 28 1,347 846 13 65.08 14 894 590 5 118.00 -52.92

Actually, it turns out that the majority of Somerset bowlers have done better in division one than in division two. That Suppiah ends up at the bottom of both lists reflects well on the way he has improved as Somerset have faced the challenge of top-flight cricket (though, admittedly, his first division average is still over 50).